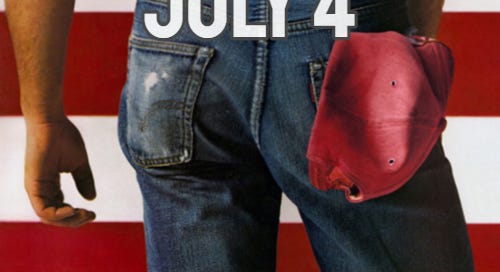

July 4, 1997

"This Whole Thing Smacks Of Gender," i holler as i overturn my uncle's barbeque grill and turn the 4th of July into the 4th of Shit

But the song didn’t mean anything, just a call

to the field, something to get through before

the pummeling of youth.

— Ada Limón, “A New National Anthem”

Dean and John didn’t talk on the drive down to Missouri’s for the party. The only thing Dean wanted to talk about was Sam, and it was better not to broach it. John might say something harsher than he already had, or make a decision in a fit of temper that they couldn’t walk back from. Dean only travelled with him at all because he had to stop John from killing himself driving home piss-drunk.

Missouri lived in one of the bigger, older properties with a Victorian house set far back from the road, surrounded by rolling fields. The corn coming in was closer to waist- than knee-high by the fourth of July, and the wheat was turning brown ahead of schedule. Dean had the same urge as anybody who grew up in these parts to mark these things, understanding how personal fates were wrapped up in the unpredictable whims of nature. Missouri, however, always had a sixth sense about what to plant and when to harvest. She was better than any Farmer’s Almanac.

They parked among the other trucks and cars on a stretch of bright green lawn beside the lane. John wasted no time in plopping down a camp chair and his cooler, reaching in for a can, opening the tab with a finger before he’d even closed the cooler lid.

Dean carried a heavy crockpot of pork ribs to one of the tables, directed by Missouri as to where to set it down. She put a hand on his shoulder, spoke to him in such a nice way about how popular the dish had been last year. It effected a fast smile out of Dean, but in the way Missouri always had of making him feel shy. She always acted sympathetic towards him when he didn’t know what he’d done to deserve it.

Or maybe it was just so, when she said something about moving a couple of the borrowed picnic tables, he offered to help without being asked.

He preferred working, truth be told. He would’ve rather been assigned a laundry list of chores to keep things running than to try and fit in today. He woke up feeling out of sorts, muddled by life’s recent series of unclosed brackets. Dizzy nights and unfocused days, like there was something lingering in the corner of his eyes that disappeared every time he tried to turn his head to face it. If he could only have been useful, he wouldn’t have to live with himself.

He tried to relax into the party like he was supposed to. He set up his chair near Bobby, who’d somehow managed to convince Rufus to come. Rufus sat back in his lawn chair with a stern expression, betraying a twitch of distaste now and then as the circle of guests around them drank and bantered. There were games for the kids, badminton and horseshoes, but they were well below Dean’s age to join in. Jo was away at her competition for the weekend, travelling with a friend’s family while Ellen stayed here in town. Everyone in this crowd was at least ten years older than Dean. He had no place in their conversations and didn’t do much to invite himself in.

The sun dragged above their heads, drying everyone out and making the alcohol hit faster. Someone brought a six-disc CD player hooked up to speakers to keep the music going, playing one tracklist of high-energy rock and country Americana after another. Sweat trickled down the back of Dean’s neck and whenever he moved he felt his skin unsticking to every surface it came in contact with. Chatter and laughter and drunken boasting rose around him. He was surrounded by people but had never felt so intensely lonely.

Dean got up without bothering to excuse himself, heading in to see if he could get a glass of ice water or sweet tea. There were soft drinks in the coolers, but he wanted to get away from the din outside.

The house was mercifully cool, the brisk air conditioning working against the sweat on his skin. His shirt stuck to him and he pulled it away from his neck by the collar, searching for a reprieve.

Dean knew his way around just a little from previous years of celebrations. He helped out, too, when Missouri needed extra workers for the harvest, and she always served a good dinner inside at the end of those long days. The kitchen lay at the end of a narrow hallway panelled in dark wood, past a couple of sitting rooms. The other rooms were old-fashioned and Victorian, but the kitchen had bright countertops and new appliances, standing out against the original cupboards. He would’ve loved to make food in here with all the space it had.

He allowed himself to daydream about it a little as he filled a glass with water and ice. He leaned against the counter and tried to make the water last, prepared to stretch out this sojourn as long as possible.

He wasn’t the only one stealing a respite from the heat. He heard a set of familiar voices from another room that winged off the kitchen. Muttering about the temperature, how “Everything sticks...”

He shifted enough to glance into the living room, unseen by the pair within. Jody and Ellen sat on the couches, Ellen tugging at the front of her blouse to get air the same way Dean had, and Jody with a loose posture, limbs stretched out. She looked like she’d rather be in a bathing suit than a dress.

As far as company went, it was a toss-up. He didn’t know whether he was prepared to be social or not. They certainly didn’t need him and, while he didn’t intend to eavesdrop, in this rare urge for solitude he wasn’t inclined to interrupt. He’d finish his water shortly and go.

“And I’m not sure if it’s me or all the sun,” said Jody, “but Missouri’s lemonade and gin is—”

“Ohh, there’s danger for you,” said Ellen with a low laugh, She carded her fingers through her hair, letting the heat out of it. “Now you’re really one of us.”

“Hey now. I’ve lived here for five years and everyone acts like I’m still the… the Johnny-come-lately. Do you know how hard it is to do my job when I’m up against this… this deep-country code of silence? There’s all this town history. All these characters. Old bitterness. Family secrets. And nobody talks about it.”

While he didn’t mean to listen, Dean found himself a little curious. Jody had a point. The older he grew, the more he glimpsed the edges of buried feuds and sorrows. Complicated networks of family marriages and personal scandals. People who wouldn’t speak to each other over something that happened forty years ago. People you couldn’t buy livestock or property from on principle, because your friends and kin had been wronged by theirs.

In the past week alone, he’d seen more. Family secrets and hidden doings and things that never came to light: unmentionable histories.

“Isn’t that the case everywhere?” Ellen asked. “The past is the past. Sounds like you want clairvoyance. You should try Missouri. She used to dabble a little.”

“No,” said Jody emphatically. She took another sip of her drink, then rested her head heavily against her fist. “I just wish people wouldn’t zip right up when I’m trying to help them. There’s so much pride in people around here, but it’s not doing them any good.”

“Like what?” said Ellen, opening her eyes and looking over. She seemed at least mildly entertained by Jody’s complaints. “Pride’s not always a bad thing. Give me an example.”

Jody groaned, turning her forehead towards her fist and shaking her head, squeezing her eyes tight. “Oh, I don’t know,” she said. “Because no one will tell me.” She looked across at Ellen, squinting as if to keep from seeing double. “You know John Winchester pretty well?”

Dean froze. He curled the glass in his hand towards his chest, wanting to keep himself contained, keep from making a sound. He should really intervene. He should let them know he was here. He couldn’t move.

Ellen spoke carefully, not as drunk as Jody. “Sure,” she said. “I’ve known him a long time.”

“What do you think of him?”

“Good at his business,” said Ellen. “Keeps my daughter employed.”

“Nice man?” Jody asked.

“Not particularly,” said Ellen.

“And his boys,” said Jody. “Dean and Sam?”

“Nice boys,” said Ellen.

“Not what I was asking,” said Jody. “As a parent, what do you think of him?”

“I don’t see what goes on,” said Ellen. “I wouldn’t know.”

“But you think something goes on,” said Jody.

Dean didn’t want to hear this. He ought to leave this room and go back outside and pretend none of this was happening.

Ellen’s gaze turned a little distant. “There were times when I—” She stopped herself. “But if I really knew then I’d— Are you investigating something, Jody?”

“I’m not even sure,” said Jody. “If I was, I really shouldn’t be talking about it.” She tried to pull herself to sit up straighter. “I shouldn’t be talking about it anyway.”

Ellen still looked distant, tapping her fingers on her glass.

“Just the thing is,” said Jody, rallying, “I can put one and one and one together. Alright? War vet—”

“Volunteer,” Ellen said. “Joined when he was still underage.”

“Previous assault charges. You’d know about that.”

“Happened outside my bar,” said Ellen.

“Settled both times. But: a history of aggression.”

“Mean drunk,” said Ellen. She lifted her glass but paused before she took a sip. “And he’s often drunk.”

“One kid has gotten the hell out of this state, hundreds of miles from his family and home, while the other walks in his shadow.”

As much as anything before it, this socked Dean in the throat. It was unfair to him. Dean didn’t walk in John’s shadow. It was only that John was so good at blocking out the sun.

“I just don’t trust it,” Jody concluded with a sigh.

Ellen chewed on her lower lip. “I don’t know anything,” she said at last, speaking slowly. “I’ve never been able to tell. Dean gets injured sometimes. But he does rough work and a few scrapes and bruises around the farm aren’t unusual. Lord knows I see how careless Jo can be. And getting two black eyes being thrown from a horse, well. It’s not impossible. It’s a long way to fall and a lucky thing to break his arm instead of his neck. But there was something that didn’t sit right with me about this last instance.”

“Go on.”

Ellen looked up from the middle distance to meet Jody’s eye. “Who breaks in a young horse at that time of night?”

“I had the same question,” said Jody.

“And Dean wouldn’t talk?”

“I can’t make him,” said Jody, shaking her head. “Maybe I’m wrong. Maybe there’s nothing going on. Or maybe there is. He’s an adult, though. Unless he were to reach out about it, there just aren’t the same supports for intervention. And if he doesn’t want to leave, or doesn’t think he can leave, no one but him can change that.” She drank the last of her lemonade, the ice clinking in the glass as she lowered it, a finger raised. “But if that’s what’s happening—if, mind—and all he does is shove it down and hide it away? I’ll tell you what’ll happen. It’ll just cycle on through, handing down that damage. I’ve seen it before, Ellen. Ten or fifteen years from now, when he’s got kids of his own, I’ll be right back here searching for proof.”

At the other end of the house, the front door opened. Jody and Ellen glanced over to it idly, sightlines never crossing his way, still unaware of Dean’s presence.

He had to leave now. He set down the glass of water on the counter and made for the kitchen’s sliding door, quick and quiet through years of practice. He exited out onto the small back deck. Everyone else lingered at the front of the house where the barbeques and tables full of food and drinks were to be found. Here he faced the long, horizontal rows of vegetables that grew on a small hill, the equipment shed with tall grass growing around it, the rows of polystyrene beehives underneath the pear trees.

He didn’t want to be seen by anyone. He couldn’t run, he couldn’t leave. Instead he descended the wooden staircase and saw a hollow place next to the steps that spoke to his instinct to curl up and hide away. No one would think to look for him there. There was just enough room for him to set his back against the latticework around the deck, to wrap his arms around his knees, shadowed by the angle of the high house and the raspberry-rose blooms of a flowering spirea next to him. He bowed his head against his forearms.

His thoughts moved too quickly for him to make sense of. He felt like he was supposed to be in physical pain, like every beat of that conversation hit him harder than actual blows ever could. Far around the other side of the house, music carried quietly in the breeze, bursts of laughter breaking out. They were putting the food out, with the scent of charcoal and grilled meat flavouring the air.

He couldn’t make himself get up. He just needed another moment. Another moment.

He froze when he heard the sliding of the patio door. He couldn’t say how long he’d been here, but it shouldn’t matter. No one would be looking for him. No one would check this shadowed corner for him.

The door slid shut again and footsteps paced across the deck and Dean prayed not to be noticed. He heard a soft sigh, then, after another moment, someone started down the steps.

As in the kitchen, Dean could see more than be seen. And he knew the angled slope of those shoulders, the dark hair that stirred in the breeze. Cas didn’t look back, making in the direction of the hives.

“Cas,” said Dean.

He didn’t mean to speak at all. He didn’t intend to announce himself.

Perhaps it was better to call his attention than wait on the risk that Cas would finish his tour and spot him in hiding.

Cas turned at the sound of his name, expression changing when he saw Dean. “There you are,” he said.

He didn’t ask what Dean was doing in somebody else’s flowerbeds. Instead, he stepped in among the leafy shrubs and flowers and settled himself next to Dean on the red cedar mulch.

“Bobby said you might’ve gone inside,” said Cas.

“Was anybody looking for me?” said Dean.

“I was,” said Cas. “I was hoping you were here. Here at the party, not here—” he looked around himself now, “—in the garden, exactly.”

Dean couldn’t say how good it was that if someone was looking for him, it was simply Cas, who wanted nothing Dean didn’t already have in him to give.

“You’re not having fun at the party?” Cas asked.

Dean shifted a little, adjusting his hold around his knees then once more lowering his chin to his arms. His knees poked out from the frayed holes in his jeans. He gave a faint shake of his head. “I’m just in a kind of weird mood,” he said, and it felt painful to even say that much. He pressed his eyes shut tight.

At his side, Cas’ arm lined up with his own, a casual and careless meeting of bodies. Summer-heat and skin, the firm and lean muscles of labour in each of them. There was something grounding in how physically present Cas’ body was next to his, not just an idea but an absolute. Grounding and somehow more overwhelming. Dean wasn’t ready to open his eyes.

“Well, I like this spot,” said Cas, picking up a few of the red woodchips to examine, then shifting them between his fingers to let them fall to the ground again.

It was strange that Cas’ presence didn’t disturb the solitude Dean so badly craved. He wanted to escape reality, but he could do it with Cas. If anything, Cas provided another means of burying himself deeper. He wanted to rest his head on Cas’ shoulder and turn his face further from the real world by hiding against Cas.

He strained against the impulse, trembling with how much it took from him to not do that. He squeezed his arms tighter around his knees.

If he didn’t say something or do something, he would come apart entirely. He tipped his head back against the boards behind him. He swallowed hard and said, “Cas? You think you’ll have kids one day?”

Cas’ childhood remained a mystery to Dean. One of those deep-country silences that Jody spoke of. He’d had a fractured upbringing. He pulled himself out of it. If there was anyone who could give Dean hope, surely it was Cas.

Cas didn’t look at Dean, going still beside him. “No,” he said after a moment. “Probably not.”

“You don’t want a family?” Dean asked. It wasn’t an instinct he could understand. All he wanted was family.

Cas frowned faintly and passed his hand over one of the fronds of the shrub to his left. “Those are two different questions,” he said.

Dean opened his eyes, studying Cas’ profile. He wanted a family but didn’t know about kids. Dean didn’t know what to ask next, trying to puzzle it out on his own.

“Why do you ask, Dean?” Cas said, turning his head to look at him now. His gaze, always arresting, had never been quite this near. The space between them was nearly nothing. In the shade of this makeshift bower, Cas’ eyes became such a deep, oceanic blue that Dean felt like he’d been pushed underwater.

He looked away, drawing his arms in, trying to keep his hands and posture loose but he could feel the trembling in his fingertips. He was too sensitive today, already done in by the hot sun and the tension of the day and that eavesdropped conversation. He felt like an exposed nerve. Even the touch of air would sting and make him shudder.

“I just— Do you ever worry you’ll turn out like your parents?” said Dean.

Cas dropped his gaze, his head bowing as well. “Oh,” he said.

“I’m sorry,” said Dean, tripping over his words. “You don’t want to talk about it. I’m not asking you to tell me anything. I get it. It’s none of my business. I’m sorry.”

“It’s not that it’s none of your business,” said Cas. “I’ve— I’ve tried very hard to leave it behind.”

“Has it worked?” Dean asked. He didn’t mean it as a challenge. His eyes wide with sincerity, a lighter and clearer green than the leaves of the plants around them. He wanted to know if he stood a chance.

Cas didn’t rush to an answer. Finally he said, “Less than I’d like. But more than I’d hoped.” He tilted his head to one side. “Families can be complicated. I think you know that.”

Dean gave a faint nod of his head. He didn’t speak. He always had a keen sense when Cas would say more, and an even keener longing to hear it.

“If I had a family, I hope I wouldn’t turn out like my parents. I would want to spend time with my children and be patient with them. To let them grow in whatever direction they needed. Help them to, even. I would want to love my spouse. I would want…” He turned his head away from Dean and looked out towards the distance. Vegetable rows ahead of fields with golden wheat. The sun took on its first shade of orange, hitting the evening atmosphere.

“I would want country air and animals to look after and for us, all of us, to know we belong there. Are wanted there.”

Dean ached too much to stop himself. He turned his face and bowed his head to rest on Cas’ shoulder, eyes pressing hard-shut again. He let his weight lean against Cas. It was this or tears, this or crumbling to dust because he’d held everything together too tightly. Cas startled only a little, then his body shifted, loosening in an inviting way.

“Dean?” he said.

Dean couldn’t speak. He didn’t know what he’d say if he opened his mouth, but he knew it would be dangerous. It was just that, what Cas described— it was everything Dean wanted. He wanted to be there with Cas in that imagined paradise. He wanted to belong and be loved. He wanted to give his love to someone and not just hand down the strife he’d been raised with.

“Dean,” Cas said again, more quietly. He lifted his hand and slowly he stroked his fingers through Dean’s hair from his temple to the back of his head. Dean turned his nose towards Cas’ shoulder and Cas did it again. Then again.

Dean wouldn’t dare to move and break this apart. His chest rose and fell. He could feel his heavy heartbeat. Could hear the thud of Cas’ too. He felt dizzy, like he was losing his grip on the world. He didn’t want to ever return to it. To gossip, to consequences, to confusion.

Cas’ fingers combed back Dean’s hair again, but this time they trailed further, down to the fine, sweat-soft hairs on his neck. Cas’ hand briefly cupped around the back of Dean’s neck, holding him. Dean’s posture slackened and he turned towards Cas all at once, girding an arm around his body. Cas’ other arm encircled Dean’s waist, shaping to him.

He hadn’t known how much he needed this. Even as it answered something in him, his heart tensed in apprehension, then released. Tightened with the whirl of his thoughts, unwound at the genuine solace. He should be ashamed that it took so little with him. One embrace and he came undone with the approval, the relief.

Cas smelled fresh, sharp, masculine. His body so solid, his hold so strong. Stubble grazed against the ridge of Dean’s cheek.

Holding Lisa never felt like this. She was soft where she wasn’t bony, she was tiny in his arms and he always had to condition himself accordingly. She didn’t light him up with security, with salvation.

He wanted to burrow deeper into Cas. To be chest to chest, to carve a space for himself within Cas’ ribs. When he took in a breath, his nose in Cas’ collar, he met the scent of vetiver and sage. He wanted to fill his lungs with Cas. He wanted to turn his face up and press his lips and tongue to the column of Cas’ throat and taste the salt of his skin.

Dean ripped out of the embrace gracelessly, tearing apart something that had been delicate and unsayable. Something strangely mortal. Cas’ face betrayed some surprise, his arms parted as if unprepared to concede that Dean left them.

“I’m sorry,” Dean said quickly, anxious to fill the gap between them. “I’ve just been all kinds of messed up today. I shouldn’t’ve—” He pressed his lips tight and shook his head, then dragged his hand through the hair Cas had so recently carded his fingers through. He shouldn’t have been thinking the things he did. He was just confused, had just been thinking about Lisa, and wasn’t used to any touch that took the shape of affection. Cas couldn’t know all that. Cas hadn’t done anything wrong.

“Are you… okay?” Cas asked, one hand reaching for him, then halting again.

“I’m fine,” Dean said. He twisted himself around to kneel, then stand, pushing off the ground. Cedar chips stuck to his palm, then fell away. “We should get back to the party. I’ve been gone too long.”

“You don’t have to be at the party,” said Cas, reaching for the boards of the deck above him as he stood. “You don’t sound like you want to be.”

“It doesn’t work like that,” said Dean.

Cas angled his head, eyes narrowing. “You’re allowed to leave,” he said. “I could take you— I could go with you. I’d drive you anywhere. Anywhere you wanted.”

Dean shook his head. He didn’t know how he was supposed to explain something so essential to somebody who didn’t automatically understand it. He’d already pushed too far against the confines of what bound him as guest, as neighbour, and most especially as son. As everything Dean Winchester was expected to be. He had a role, and he’d lose everything if he didn’t play it.

“Not this time,” Dean said. He turned to leave, heading back around the side of the house. After a moment, Cas caught up with him. They walked side-by-side, but with more distance between them. Dean could still have reached out to touch Cas, but only just.

Cas didn’t meet Dean’s eye again. He wore a troubled expression, didn’t seem particularly interested in food and had to be talked into picking up a plate by Dean. Beyond coercing him to eat, Dean didn’t know what to say to Cas anymore. He sat with Bobby again, balancing his full plate and trying to play off that he didn’t know the food was up already.

Cas joined but said little. Before long he stood to cross paths with Missouri, talked with her a while, then returned to where Dean sat to say he was going.

After all that had passed between them, Dean had the odd sensation he was supposed to stand and hug Cas goodbye or walk him over to the motorcycle parked in the lane. Something to signify their connection. But he was under the eyes of others at the party. Bobby, Rufus. Down the lawn, John was drinking a beer and watching some of the men set up a bonfire, offering advice but doing nothing to actually help.

So he just said, “Yeah, see ya,” and prayed his summer tan hid the flush of heat that rose to his cheeks. Cas departed and all Dean could think was yeah, see ya on repeat in his head.

Dean slept poorly that night, sucked into a dream where he lay in his bed with a fever. Sheets damp, skin hot, insides twisting. It was an antiquated kind of sickness and someone sent for the doctor, and the doctor who came with his black medicine bag was Cas, as Dean knew it must be.

Cas sat on the edge of the bed at Dean’s hip and placed a hand on Dean’s forehead to feel his temperature. His touch eased Dean so that he caught his first breath again, although it didn’t treat the underlying fire in his veins. Still, it was enough that he looked outwardly calmer, that he ceased quivering with his ailment. Cas calmly decided that his condition was improving and he could be trusted to make a full recovery from here.

When he stood and took his hands off of Dean, Dean felt terrible once more. His body shook so badly his teeth chattered and Cas quickly swept to his side again. He placed his hands on Dean’s bare collarbones, then flat against his sweat-damp chest that glistened under the candlelight. Dean’s body eased back into his mattress. Cas assessed him with steady, half-lidded eyes and moved his hands to Dean’s sore shoulder. He traced touches down his arm, then tangled with his fingers, splaying them out as he’d once done in playfulness in the stables of the barn.

Cas let go and stood up once again, and this time Dean wasn’t really sick, not terribly, but he couldn’t stand not to have Cas’ hands on him. He pretended to shiver, to moan in pain, to reach out in desperation. Cas would come back, then leave, and Dean would pretend all over again with this see-through routine. Only so that he could let his head hang back limply when Cas’ firm hand clasped the back of his neck. So that Cas’ hand would slide against his ribs and his arm curl around Dean’s body to soothe him with touch. Like he could heal everything wrong with Dean if he just never stopped touching him.

It became a hotter, heavier dream when it was no longer sickness in his veins but a thick ache that made his body harden. He wouldn’t be well again unless he broke the heat. And Cas, his physician, might’ve half suggested Dean could care for it on his own, an unspoken dream-murmur that permeated the air. But Dean insisted no, offering thin excuses in the same way he faked sick: that it wouldn’t be enough. That things may be fatal if not correctly ministered, and with death on the line, it could only be an expert that saw to it, an impartial handler.

Dean’s face hid once more against Cas’ collar, his breaths short and fast against Cas’ throat, while Cas rubbed the palm of his hand over the front of Dean’s boxers. He knew the rhythm Dean needed, the build-up. Knew better than Dean ever would what his body required. Cas wrapped his hand around him and said into his ear, voice low and gravel-rough, “Dean.”

Dean woke gasping, shuddering, feeling sated and blasphemous all at once. He swore he heard his name spoken aloud in this room. Too real, too familiar.

He sank back still trembling, left with the vivid awareness of the dream’s every moment.

He covered both hands over his face. It was only a dream. It was only a dream.

One of my favorite chapters <3